By Tom Swift

Staff Writer

Imagine all these people around you can read. You want to read, too. But you cannot.

The person who controls your fate, day-to-day? He can read.

The person you work with all day? She can read.

Boys and girls your age? Older? Younger? The children you see when you wander about the neighborhood? Yep. They can all read.

You? No. You cannot. You can't read, even though you want nothing more, because no one will teach you.

Circa 2024, many people don’t self-identify as “readers.” Yet even the least inclined among us read words every day. Most of us read tens of thousands of words. Reading is a required human skill. It’s the primary pathway to learning. We read in order to grow. Reading is essential for personal autonomy.

Frederick Douglass, like other enslaved people in 19th century America, was forbidden from learning his ABCs.

In response to this denial of basic human freedom Douglass did something radical: he learned them anyway.

Douglass tricked white boys in the neighborhood into teaching him how to sound-out words. He would, if he had to, use his meals as payment. Wherever he went, if there were written words to be found, he picked them up — shards of discarded newspapers were a common source of stray sentences. He plucked them from the tops of garbage cans. He would swipe notes and papers and signs and other bits blowing about and hide them. Later, when the coast was clear, he would engage in covert independent study.

The discipline and patience required to fashion these stolen words into a self-guided course in reading staggers the mind.

Comprehension of the few short unremarkable paragraphs I have written thus far in this post would have taken the young Douglass weeks to learn.

Had he merely acquired enough written English to get by — that would have been a feat. Except he did so much more than that. He read Shakespeare. He read Robert Burns. He read and memorized the same Bible the people who enslaved him devoted their daily lives, and their Sunday sermons, to. This included the Book of Exodus — included, in other words, Scripture slave-holders didn’t want slaves to know existed.

When Douglass grew up and established his own home, he filled it with books. He became a self-directed scholar. A personally produced public intellectual. He drove himself to become such a skilled rhetorician that, even as a former slave during a time when many Americans were willing to die in defense of the institution, he was invited to the White House. Invited not as a guest. Not for tea and a tour — but to give counsel to President Lincoln.

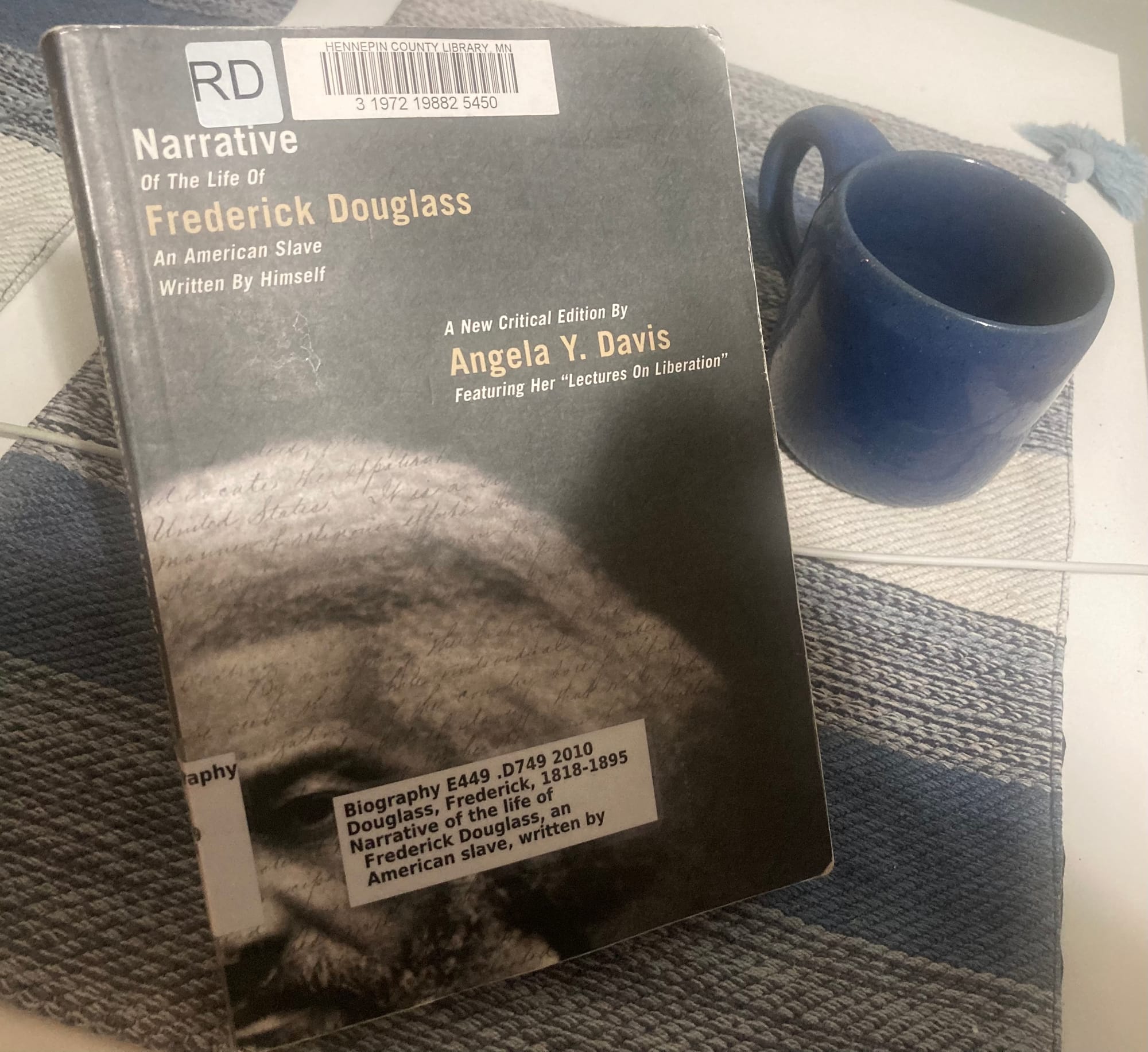

Douglass not only more or less taught himself to read. If you were to boil his life’s work down to any one profession you would have to call him foremost a writer. He started an influential newspaper. He edited others. He wrote articles and screeds and speeches. (He gave speeches all over the country and even abroad.) In his mid-20s Douglass wrote what would become a classic: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, the first of multiple memoirs, a book that should be read not only as an essential part of the historical record but also as a standalone work of literature suitable for placement alongside the books that lined his home.

If Narrative was assigned to me in high school, I don’t recall that. Possibly I was too focused on hockey to notice. Either way, I recently righted that wrong. In so reading his factual, never sentimental, spare and clear sentences it occurred that people could study the self-taught reader’s writing if their objective was, in the spirit of Douglass, merely to teach themselves how better to write.

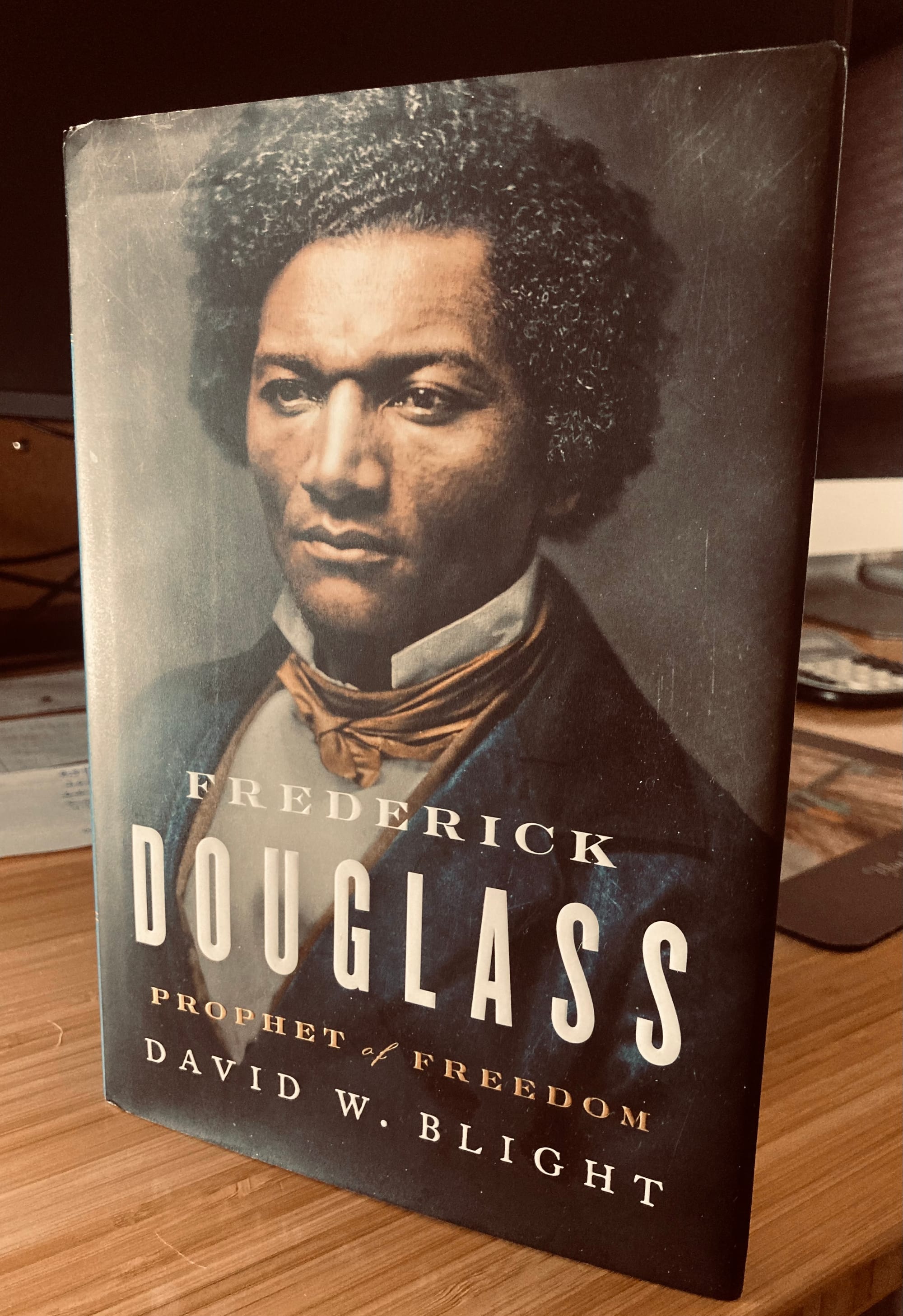

I also recently read David W. Blight’s Pulitzer Prize winning Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, a comprehensive and compelling work that, among other things, shows the institution of slavery through the unique lens of the life of Douglass (after he escaped slavery, Douglass devoted his every effort to abolitionism, the Civil War, and later Reconstruction).

One of the blunt impressions that came forth for me during these readings pertains to what today we might call social contagion. I couldn’t help but wonder how many slave-owners and their families did what they did — treating human beings as if they were farm equipment — because they didn’t consider any other way. Or if they did consider any other way they didn’t have the strength to act on that inner knowing. That they didn’t have the wherewithal to counter what everyone else in their sphere would say or do. I couldn’t help but wonder how many people just followed the crowd.

The juxtaposition hits you as if Blight’s tome had been thrown against your forehead: Douglass swimming against a torrent to teach himself to read in a world where tens of thousands were unable or unwilling to so much as question a prevailing paradigm that had them denying the humanity of men, women, and children living under their own roofs.

The brand of Christianity commonly practiced at the time was not the only thing that upheld the cruel institution. But it was a major force, maybe the single greatest that convinced people to believe they were doing God’s work when they were delivering bloody lashes to the backs of men and permanently separating toddlers from their mothers. Whether or not given slaveholders ever cracked the “Good Book,” they undoubtedly practiced a religion — believing on faith that their behavior was righteous.

During a recent group discussion of Narrative I asked a rhetorical question: What today might be an example of a massive human blind spot? To be sure, there are no comparables to slavery (then or now). The answers I got back were of the sort you might think: treatment of animals on factory farms was one example. I appreciate that someone might think of that, which is a blight on us all. However, in asking the question I didn’t mean to conjure a future rear-view of what good today will later be seen as evil. By my question I meant to wonder: What social forces leave us blind to what should be different, better?

I was thinking not only of wrongs we could right but also of practices that leave us unthinkingly believing things on errant or incomplete evidence. In which we, say, draw actionable conclusions about society based on a 10-minute YouTube video or an article liked by our friends on Facebook. Tweets and posts show up in our feeds that give us impressions about our towns, our country, the world that are not at all representative but that, given the intensity of the sensory experience of online life and the real or imagined presence of others who agree-disagree (everyone has an opinion on everything), register in our minds as urgent alarms.

But are they? What does the evidence show? What are experts saying? (Here I mean people who have spent hours and hours — at least multiple months, usually one or more years — examining the data and arguments.)

Since we can’t fathom that we ourselves would have engaged in evil practices of the past — we can only imagine we would be on the right side of issues in which the wrong side was so wrong the mere thought would make us spit up our Starbucks — we think it follows that we have clarity about the events of today. It’s hardly a hot take to say that is an illusion.

It’s not, in fact, easy to see the world clearly right now. If it ever is.

It’s even harder to go against prevailing views. Sometimes, given the power of life online, it feels like the whole world is watching — or could be — and is both ready to condemn and with the means to make that rebuke stick.

Of course, unlike for a young Frederick Douglass, the world isn’t telling us we can’t read. But it is actively working against our capacity to understand.

How many of us are as brave as Douglass? How many of us follow the voice inside that knows what is right? How many of us are as innately driven to be and express who we are even if the world wants us to be something else?

The following slice of Narrative (1845) jumps off the page (this text comes by way of Project Gutenberg; I read a 2010 Critical Edition, edited by Angela Y. Davis) for the way Douglass describes the inner knowledge of what he had to do, the world be damned, and the outer awareness of that world.

My new mistress proved to be all she appeared when I first met her at the door, — a woman of the kindest heart and finest feelings. She had never had a slave under her control previously to myself, and prior to her marriage she had been dependent upon her own industry for a living. She was by trade a weaver; and by constant application to her business, she had been in a good degree preserved from the blighting and dehumanizing effects of slavery. I was utterly astonished at her goodness. I scarcely knew how to behave towards her. She was entirely unlike any other white woman I had ever seen. I could not approach her as I was accustomed to approach other white ladies. My early instruction was all out of place. The crouching servility, usually so acceptable a quality in a slave, did not answer when manifested toward her. Her favor was not gained by it; she seemed to be disturbed by it. She did not deem it impudent or unmannerly for a slave to look her in the face. The meanest slave was put fully at ease in her presence, and none left without feeling better for having seen her. Her face was made of heavenly smiles, and her voice of tranquil music.

But, alas! this kind heart had but a short time to remain such. The fatal poison of irresponsible power was already in her hands, and soon commenced its infernal work. That cheerful eye, under the influence of slavery, soon became red with rage; that voice, made all of sweet accord, changed to one of harsh and horrid discord; and that angelic face gave place to that of a demon.

Very soon after I went to live with Mr. and Mrs. Auld, she very kindly commenced to teach me the A, B, C. After I had learned this, she assisted me in learning to spell words of three or four letters. Just at this point of my progress, Mr. Auld found out what was going on, and at once forbade Mrs. Auld to instruct me further, telling her, among other things, that it was unlawful, as well as unsafe, to teach a slave to read. To use his own words, further, he said, “If you give a nigger an inch, he will take an ell. A nigger should know nothing but to obey his master — to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best nigger in the world. Now,” said he, “if you teach that nigger (speaking of myself) how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.” These words sank deep into my heart, stirred up sentiments within that lay slumbering, and called into existence an entirely new train of thought. It was a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things, with which my youthful understanding had struggled, but struggled in vain. I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty — to wit, the white man’s power to enslave the black man. It was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom. It was just what I wanted, and I got it at a time when I the least expected it. Whilst I was saddened by the thought of losing the aid of my kind mistress, I was gladdened by the invaluable instruction which, by the merest accident, I had gained from my master. Though conscious of the difficulty of learning without a teacher, I set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read. The very decided manner with which he spoke, and strove to impress his wife with the evil consequences of giving me instruction, served to convince me that he was deeply sensible of the truths he was uttering. It gave me the best assurance that I might rely with the utmost confidence on the results which, he said, would flow from teaching me to read. What he most dreaded, that I most desired. What he most loved, that I most hated. That which to him was a great evil, to be carefully shunned, was to me a great good, to be diligently sought; and the argument which he so warmly urged, against my learning to read, only served to inspire me with a desire and determination to learn. In learning to read, I owe almost as much to the bitter opposition of my master, as to the kindly aid of my mistress. I acknowledge the benefit of both.

I ask again: How many of us are as brave as Douglass? How many of us follow the voice inside that knows what is right? How many of us are as driven to be and express who we are even if the world tells us to be something else?

Are we similarly willing to take on the forces aligned to keep us ignorant? To use everything directed at us, even unpleasant words and unkind actions, to make ourselves better? To sneak, if necessary, to learn as much as we can? To turn ourselves into highly learned human beings? Independent thinkers even if that means going against our team, our tribe, our town?

Is it in us to be that radical?